New evidence suggesting the expansion of the Universe is slowing down has been published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, in November 2025.

The new evidence, although unconfirmed, adds weight to the findings from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI), near Tucson Arizona, published earlier this year, which also questioned established wisdom about the changing expansion rate of the Universe.

Prior to the DESI publication, it had generally been accepted by cosmologists that the expansion of the Universe is speeding up. In fact, the Nobel Prize for Physics in 2011 was awarded for the observations made in the late 1990s that first showed this accelerating expansion. This led to the theory that a mysterious ‘dark energy’ of unknown origin was driving the expansion of the Universe, possibly at ever increasing rates.

This suggested an indefinite expansion where the Universe becomes cold, dark, and empty as stars die out – a scenario known as the ‘Big Freeze’ or the ‘heat death’ of the Universe. A more violent ending to the Universe was even envisaged, known as the ‘Big Rip’ where the expansion rate accelerates to such a degree that every point in the Universe would become isolated from every other point due to the finite speed of light.

However, the new evidence suggest that from around one billion years ago, this accelerating expansion reversed, meaning the Universe might eventually start to collapse back on itself. If this is extrapolated, the Universe could end up contracting back to a point of near-infinite density, like a reversal of the Big Bang. This scenario is often referred to as the ‘Big Crunch’.

Since the source and full behaviour of dark energy are unknown, it’s possible that the Universe might actually oscillate in size. It’s also possible that the Universe might have undergone many cycles of Big Bangs followed by subsequent Big Crunches over unimaginable timescales.

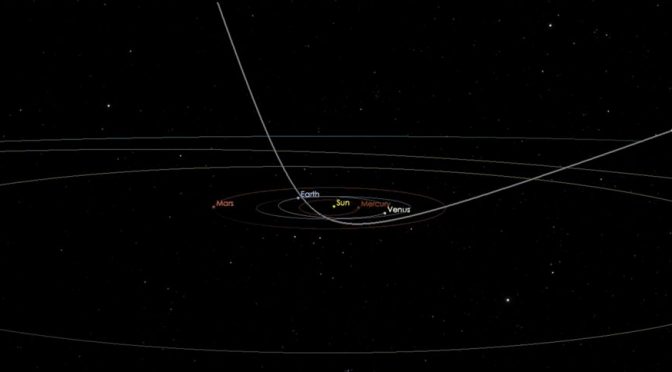

The evidence from the 1990s for an accelerating expansion was based on observations of supernovae in distant galaxies. Since theories of how these supernovae form suggest they should be of consistent brightness, it was considered possible to use this to determine their precise distance from Earth. Combining this with the supernovae’s redshift (a phenomenon predicted by Einstein’s Special Theory of Relativity), which lets us calculate the speed they are receding away from us, allows us to build a model of the expansion rate of the Universe throughout its history. This is because light takes time to reach us from distant galaxies meaning we are viewing these far-away galaxies as the were in the distant past. Contrary to expectations at the time that the expansion of the Universe was slowing down (which was expected due to the influence of gravity) it was found that the expansion rate seemed to be increasing.

However, the latest findings, bases on an alternative way of estimating the distance to 300 galaxies hosting supernovae, suggest that supernovae in the early Universe were fainter, on average, than they are now, due to variations in the properties of stars. This suggests “a time-varying dark energy equation of state in a currently non-accelerating universe”, according to the newly published paper.

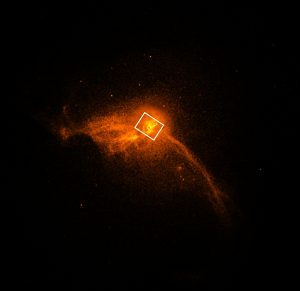

What is certain is that more observations will be needed to establish the true nature of dark energy. Instruments like the European Space Administration (ESA)’s Euclid space telescope, launched in 2023, are set to provide more data. Euclid has a wide-field imager designed to create 3D maps of the universe to study dark energy and dark matter. The featured image, below, shows a mosaic of Euclid’s observations published by the ESA in October 2024. See https://www.esa.int/ESA_Multimedia/Images/2024/10/Euclid_s_mosaic_explained

To read more, visit:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c4geldjjge0o

For the original paper, published by Junhyuk Son et al, see Strong progenitor age bias in supernova cosmology – II. Alignment with DESI BAO and signs of a non-accelerating universe, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 544, Issue 1, November 2025, Pages 975–987, https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/staf1685